Evaluating subjective probabilities in merger arbitrage

For my own edification- buying announced deals

In the previous newsletter I approached evaluating subjectively determined probabilities as it related to the practice of pricing publicly traded securities. One of the annoying wrinkles in pricing equities is the concept of “going-concern”: a business has an indefinite life and an indeterminate wind-up date, therefore the “terminal value” of a business, the majority of estimated value in a discounted cash flow analysis, by definition, can never be fungible for the minority investor.

Minority investors can never “eat” terminal value, but an acquirer can certainly do this by acquiring 100% of the business. I am not going to approach the CAPM/FP&A/capital allocation decision that comes with acquiring 100% of a business in the public market. I will approach the question of whether or not an announced deal, with a reputable counterparty, offers opportunity for reward vs. risk borne for an investor purely based on the binary outcomes of: (leaving out stalking horse/white knight bids)

A.) Deal closes → on time as planned → with cash (or properly hedge-able stock) proceeds/in the amount of the initial merger agreement at announcement

B.) Deal breaks →and is blocked by a government agency→ target shareholders are left with equity in the target in addition to a possible break-up fee

Equity investors aren’t lucky enough to live in a world of binary outcomes. In a strict sense nor are merger arb investors but I am bastardizing their practices for the purposes of simplicity.

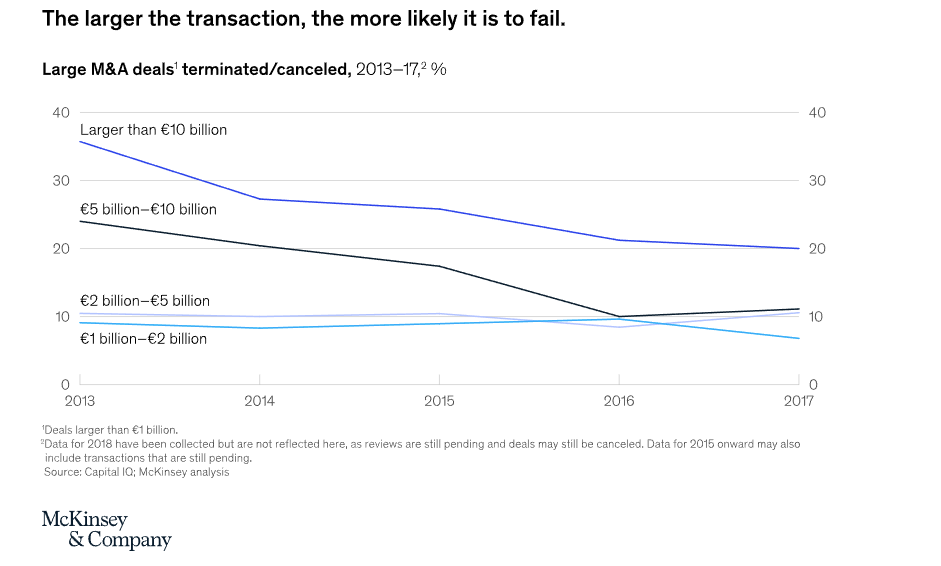

In mergers & acquisitions, past is typically prologue for the lion’s share of deals. Bankers and lawyers have meticulously streamlined and honed the process of combining legal entities into a fine science. The wild card in these situations is typically management teams that demand to do an overpriced deal for a target that will clearly face legal scrutiny from the FTC. Despite their incentives to do as many transactions as possible, bankers don’t pitch deals that will assuredly be blocked by regulators based on anticompetitive practices. This is borne out in base rate data- McKinsey concluded that only 10-20% of large deals (>1B euros) are blocked by regulators:

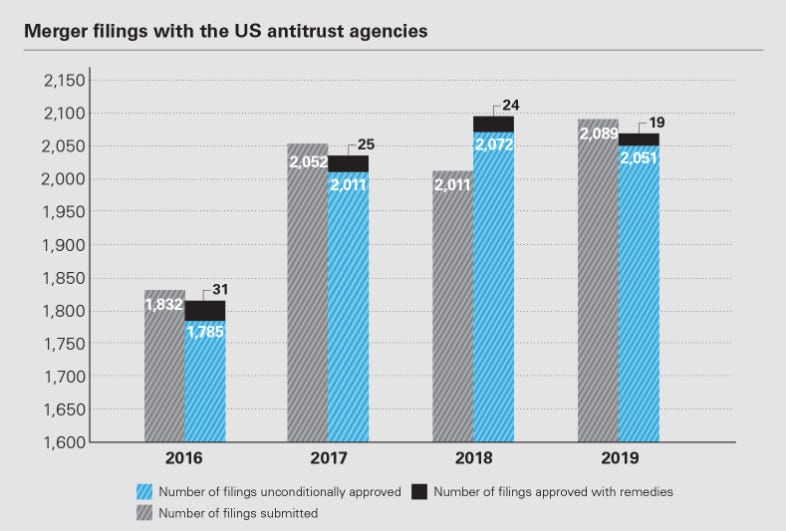

White & Case showed that between 2016-2019, the FTC & DOJ rejected just 1-2% of deals outright without a remedy:

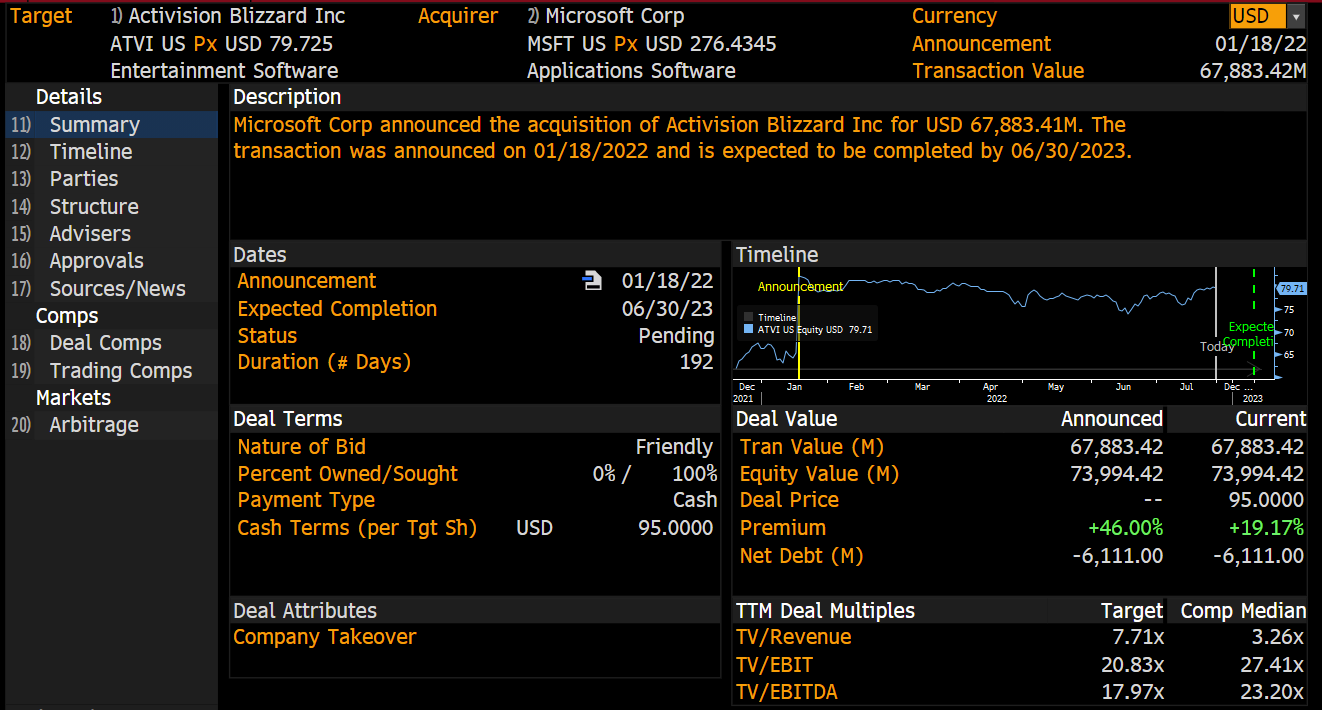

Taking a look at the ATVI/MSFT merger we can find an overview of the transaction details- the current acquisition/market premium ($95/79.72) offers a ~19% return to investors, the expected completion is June of 2023 (roughly 11 months- I’ll round to 1 year here). The current offered yield to maturity on a 1 year US treasury bill is roughly 2.8%.

One year from now, Outcome A will deliver $95/share to common shareholders of ATVI- a 19% return from current prices.

Outcome B proves more hairy to evaluate. Prior to the merger, Activision traded from a range of $40 in March of 2019 to a high of $105 in March of 2021. Prior to merger announcement the business traded for $65/share, moving averages of about $80-$60/share were the norm:

Seeing these disparate prices, it’s safe to assume that I will have to underwrite multiple Outcome B prices per share.

What is the typical unwind price of a target after a deal break is announced? Due to the paucity of announced deals being terminated in recent years, we have few historical data points to run through. Three analogous deals (if you squint) are shown below- TWX/T, TWTR, and TMUS/Sprint. Two of these mergers would later be consummated and one is still active, but all three have had dramatic swings in prices due to potential deal breaks:

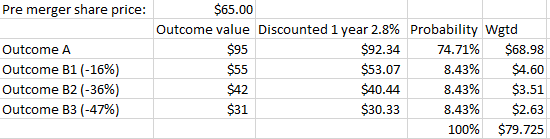

16%, 36% and a dramatic 47% drawdown in the case of TMUS/S (which was exacerbated by the outset of the COVID outbreak). An Outcome B will leave us with shares in ATVI that will see a drawdown of anywhere from -16% to -47%. I believe it’s safe to assume that these peak-to-trough drawdowns represent a fair range of outcomes for how ATVI’s share price will be affected in the event of a break.

Immediately before the merger announcement, we saw shares trading around the $65 price, which, judging from the 3 years of moving averages, I deem to be a fair representation of the shares’ value pre-merger. With these assumptions, we can triangulate what the market is pricing for probabilities of a deal break. Assuming all Outcome B scenarios are equally weighted in probability (we are estimating market sentiment, no outcome should be weighted higher than another) we can judge the probability of a deal close 1 year from now as roughly 75%, based on the current market price of $79.725:

Using our simple base rates of anywhere from 2% (low end of DOJ/FTC blocks per year) to 20% (higher end of the McKinsey study) probability of a deal break, we can make an informed call that the market, at 25% probability of a break, is more pessimistic on the deal closing than base rates would imply. This is the first step: identifying where the market is making a historically out of sample/base rate call on a given outcome.

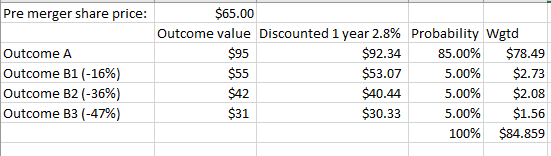

Using a shorthand, somewhat conservative heuristic midpoint of 15% probability of a deal break, we see that the proper price here should be $84.86, or a 6% implied “edge” on this bet.

Will this deal, on average, break more often than the typical announced deal with an all-cash counterparty on the other side? I have no reason to believe that it should break more often than average.

This is a starting point. The next step is to evaluate the idiosyncrasies of the ATVI deal itself and to prove the case that the market is incorrectly mispricing the likelihood of the deal closing. Has the DOJ/FTC issued guidance? The FTC has already announced it is probing the deal closely for anticompetitive practices. Does this warrant a 25% probability of breaking? I would generally disagree. This is where the fundamental analyst has the opportunity for profit.

(no positions in any of the securities mentioned here- this isn’t investment advice)

Hey this is great! No one has ever told me or even approached a base rate of deal breaks... thank you