Case studies in valuing balance sheet assets

The one-foot hurdle of valuation work

“[regarding Vodafone plc. assets] a big banana in a jar. The question is; how do you get your hand out of the jar with the banana.” - John Malone (illustration is Alice Andreini’s “Banana in a Jar”)

If fixed assets can be reasonably identified, observed and priced in a semi-liquid market with regularly available bids and offers, should they be valued on a balance sheet as such (net of taxes and other frictional costs)? There are differing, competing schools of thought here:

A.) Sums-of-the-parts asset-based valuations of businesses rarely work. They require a full liquidation of the business in order to realize potential value in fixed assets. Management will fight the board and shareholders to keep their jobs, bidders for the assets will understand this dynamic and deliberately underbid the assets. Court battles, lawyers, brokers, and other frictional costs will drain company resources as the fight to liquidate drags on, and the cash flows from the asset proceeds won’t materialize in an expeditious manner.

B.) Sum-of-the-parts asset-based valuations are a starting point and provide a theoretical economic anchor to value. After all, the market prices for fixed assets (land, buildings, ships, equipment, factories et al.) must be a theoretical reflection of the cash flows that those assets could potentially produce. Asset-based valuations must be joined at the hip with a willing & able management team; management must be incentivized to maximize the company stock price rather than their own personal W-2 income. Whatever business value you’re estimating, the value of the assets on the balance sheet must be a conservatively priced floor, not a ceiling.

Case study: Liberty SiriusXM Tracking Shares (symbol LSXMA/B/K):

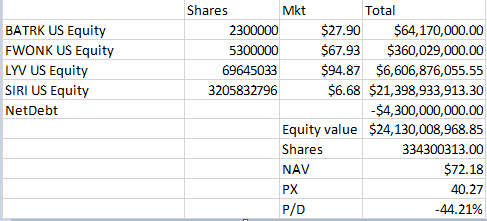

LSXMA/B/K is a tracking entity of the Liberty Media Corporation that has attributed the following liquid, listed assets:

The above grade-school level Excel table is a Rorschach test for stock pickers: school of thought A.) thinkers see a quagmire of tracking shares, multiple share class ownership, “attributed assets”, a NAV discount unable to realized reasonably, unaccounted for tax liabilities, and a management team known for extracting as much value as possible.

School of thought B.) thinkers see an opportunity to buy a basket of potentially attractive assets at a 44% discount to NAV with a management team that has acknowledged and promised to take actions to close the NAV discount. Maybe a Millennium PM sees a basket market neutral trade to potentially arbitrage. Regardless, the 44% NAV discount serves as a blinking sign: “potential opportunity”.

For some, following school of thought A is second nature. The 10x or 100x opportunities in equity investing aren’t going to be found valuing the idiosyncratic balance sheet assets of public companies. Maybe you’ll earn 10-20% every year with limited downside, but there’s still no guarantees and the upside isn’t there. Going to war with public company management teams is destructive to all parties, and the fallout hurts shareholders. The “return on brain damage” is not worth it.

For the tidy-minded, capital assets that price in semi-liquid markets typically present some of the easier-to-understand opportunities in public markets. The practitioners of this brand of modern day Graham/Schloss/“Larry the Liquidator” investing generally believe in school of thought B, usually with the understanding that assumptions for asset sale prices must be made, and those assumptions must be accurate and based off of observable data.

Read this 2016 Medium post on Maui Land & Pineapple by Stephen Vafier. An incredibly compelling thesis with lots of margin of safety, a delevering story with upside that would eventually work (the post is dated June 1, 2016- the stock price would go from $5.20 to a high of $27 in June of 2017 before meandering for the subsequent four years). This is a fine example of school of thought B.): assets are valued fairly and with observable inputs, and serve as downside protection in the thesis. This thesis, 6 years later, is still perfectly intact!

There are a few other symbols of case studies of success worth mentioning of late (VWTR, RBCN) but significant realizations of assets have occurred in recent years. The common denominator here is an activist shareholder. The lesson here, with inspiration from Bruce Greenwald: if you’ve identified an asset trading below NAV, do not buy it, there is an entrenched management team in place. Wait for the 13-D filing or for the management team to take concrete actions to closing the discount.